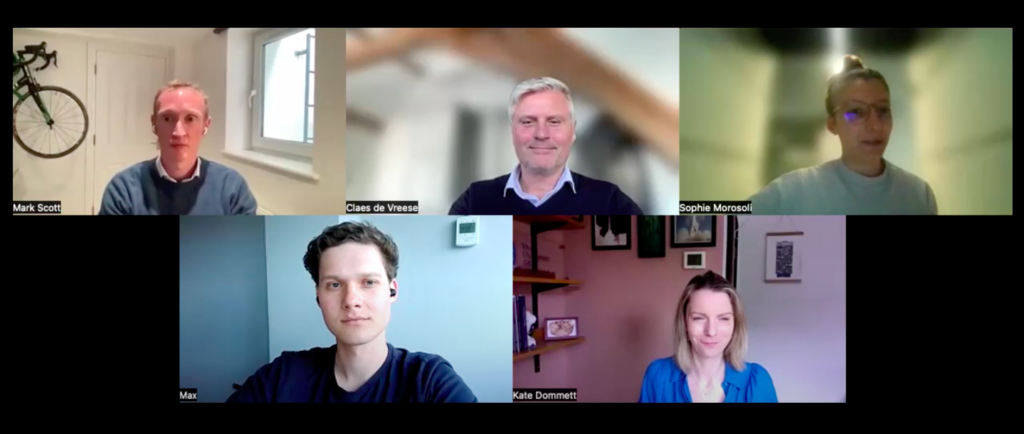

On June 6, voting day of the 2024 European Parliament elections in the Netherlands, the AI, Media, and Democracy Lab held a panel on the implications of AI technology on the week’s events. The talk was moderated by Sophie Moroscoli and Max van Drunen, who asked the three speakers to discuss their view of how AI might impact this election cycle and future ones across the globe.

While many have predicted that AI could substantially influence, or even subvert, the outcome of the European elections, Professor Claes de Vreese (co-founder of the AIMD Lab; University of Amsterdam) argued that there had not yet been a “smoking AI gun” indicating any widespread disruption. But there are plenty of more subtle ways in which AI can influence elections beyond determining the final outcome: it can change how certain issues are presented and their relative prominence, how people engage with political parties, and how campaigns orient their strategies. Understanding the entire chain of actors and AI involvement will give researchers a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of AI’s growing role in the democratic process.

This message was echoed by Professor Katharine Dommett (University of Sheffield), who emphasized the importance of analyzing the behind-the-scenes use of AI by traditional political actors. Political parties and their electoral campaigns will be heavily influenced by practical regulations and existing incentive structures: these can be readily observed and analyzed in order to evaluate the broader role of AI. Professor Dommett pointed to existing institutional AI applications, like the automation of fundraising emails or chatbots used to train volunteers. While established parties share some traits—for example, they tend to be relatively risk-averse—their approaches to AI will differ, depending on their access to resources and their place in the political landscape.

Mark Scott, Chief Technology Editor at POLITICO, provided a media perspective on these issues. He reiterated that AI had not significantly influenced the European elections—yet—and pointed to the media’s role in managing expectations and sometimes failing to do so. In his view, AI is an agnostic, apolitical tool that can be used for bad or for good: its political consequences will chiefly depend on how prominent actors choose to engage it. It is neither the origin nor the driving force behind some of the primary political challenges of our age—polarization, misinformation, etc…—but has the potential to contribute to these issues by augmenting the capabilities of bad actors and irresponsible ones.

The panellists agreed that one particular challenge was analyzing the use of AI beyond traditional electoral and political contexts—by third-party actors who are more “intangible,” harder to predict, and subject to fewer accountability protocols. The speakers also emphasized the importance of clearly describing AI’s potential applications and operationalizing its impacts—both in research contexts and in public discourse.

As a whole, the panel was a thoughtful and level-headed look at the current uptake of AI in European electoral politics. It is important not to catastrophize the possible impacts of AI technology, nor to undermine its very real risks. We would like to thank Sophie Moroscoli and Max van Drunen for moderating the talk, and Claes de Vrees, Katharine Dommett, and Mark Scott for contributing to the conversation.

Watch the full panel here: